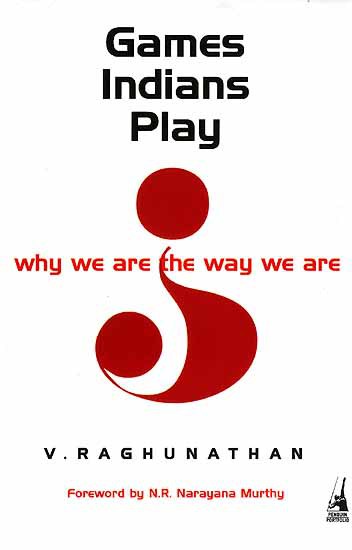

Games Indians Play: Why We Are The Way We Are

V Raghunathan

2006, Penguin.

Quick review:

This book has some good insights, but it is not for you.

Details:

The author starts off the book with this soliloquy:

“Why is my sense of hygiene so porcine? Why do I throw my garbage around with the gay abandon of an inebriated uncle flinging 500-rupee notes at a Punjabi wedding? Why do I spit with a free will, as if without that one right I would be a citizen of a lesser democracy? Why do I tear off a page from a library book, or write my name on the Taj Mahal? Why do I light a match to a football stadium, a city bus or any other handy public property, or toot my horn in a residential locality at 3am? Why do I leave a public toilet smelling even though I would like to find it squeaky clean as I enter it? Why don’t I contribute in any way to help maintain a beautiful city park? Why is my concern for quality in whatever I do rather Lilliputian? Why is my ambition or satisfaction threshold at the level of a centipede’s belly button? Why do I run the tap full blast while shaving even when I know of the acute water shortage in the city? Why don’t I stop or slow down my car to allow a senior citizen or a child to cross the road? Why do I routinely jump out of my seat in a mad rush for the overhead baggage even before the aircraft comes to a halt, despite the repeated entreaties of the cabin crew? Why do I routinely disregard an airline’s announcement to board in orderly groups in accordance with seat numbers? Why does it not hurt my national pride that in international terminals abroad extra staff is appointed at gates from which flights to India are to depart? Why don’t I vote? Why don’t I stand up or retaliate against social ills? Why is it that every time the government announces a well-intended measure like a higher rate of interest for senior citizens I am not averse to borrow my ageing parents’ names, or the family maid’s for that matter to save money? Why is it that every time the government announces no tax deduction at source for small depositors, I split my bank deposit into fifteen different accounts, with the active connivance of the bank manager? Why do I jump red lights with the alacrity of a jackrabbit leaping out of a buckshot? Why do I block the left lane, when my intention is to turn right? Or vice versa? Why do I overtake from the left? Why do I drive at night in the city with the high beam on? Why do I jump queues with the zest of an Olympic heptathlon gold hopeful?

A very intriguing start for a book about India, especially for an outsider who wants to ask these questions, but is not sure if you should.

If you ever venture to find an explanation for these things through conversations in India, blame is generally spread around to different culprits: the climate, the population density, illiteracy, colonialism, religion, or “growing up in a time where there wasn’t enough to go around.”

However, in my opinion (and the author’s too), these answers don’t stand up on their own.

In this book, V Raghunathan attempts to explain Indian’s proclivity towards these behaviors using Game Theory, specifically, the Prisoner’s Dilemma (click the link if you are unfamiliar).

The theory behind the Prisoner’s Dilemma is that an individual will usually act out of self-interest. This seems good for him individually (he defects and the other person doesn’t), but will likely end up creating a worse situation corporately (both will actually defect).

Ragunathan applies this to Indian culture as a whole. His thesis is that in most life situations, Indians always defect. He says that when put in any situation, the Indian always tries to maximize his individual short-term interests. He looks for the quick, one-time payoff that may come at the other person’s expense.

However, just like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, this choice to always defect results in a worse situation corporately, or, in the author’s assessment, explains why India still faces the challenges he quotes at the beginning, and remains significantly undeveloped.

If that wasn’t enough, the author also lists out these twelve negative characteristics of Indians, related to his theory:

- Low trustworthiness

- Being privately smart and publicly dumb

- Fatalistic outlook

- Being too intelligent for our own good

- Abysmal sense of public hygiene

- Lack of self-regulation and sense of fairness

- Reluctance to penalize wrong conduct in others

- Mistaking talk for action

- Deep-rooted corruption and a flair for free-riding

- Inability to follow or implement systems

- A sense of self-worth that is massaged only if we have the “authority” to break rules

- Propensity to look for loop-holes in laws

Most of the rest of the book jumps between Game Theory situations and anecdotal references to real or fictitious situations in India and how they can be viewed through this lens.

He associates many behaviors with Indians “defecting”: not delivering goods (on time), not delivering quality goods, not paying invoices, saying “What can I do?” to social problems, saying “What harm will it cause?” in civic issues like running red lights, and not showing care and concern for public areas.

From the outside

If you’ve ever experienced any kind of frustration with India, it is easy to jump on the bandwagon and use this as your filter. There are a few areas where I really identified with the author’s thoughts based on my experiences.

In business-to-business contracts, I rarely ever saw a “mutually beneficial” condition. When an Indian looks at the contract, either he is pleased that it is clear he got the upper hand, or he is upset that he was cheated, but will eventually use it as a longer-term strategy to later turn the tables. To put it crassly, there is always a screwed and a screwer.

The lack of long-term, mutually beneficial joint ventures is an example of this. If an Indian company enters into a joint venture and accepts a weaker role, they will often look forward to a time in the future when they can push their partner out.

I also have interacted with many small businesses and independent consultants who find it extremely difficult to get invoices paid. Invoices get lost, passed around, debated, rejected, and someone has to sit in an office everyday for a few months to get paid. It is hard to explain the reasoning behind why a company would blatantly “defect” in this way.

I interpret these things through a PowerPlays filter, but the Game Theory model might be another explanation.

The area where I most agree with the author is that selfish individual decisions lead to a much worse situation corporately. If more people would act in the good of the larger corporate group, many of these things would be taken care of.

However, there is one area of significance where I think his theory is incomplete. I find that Indians are not always making a decision based on individual needs, but rather group/family needs. Inside a group or community, people will be extremely self-sacrificing and will put their own needs below those of the group. However, if interacting with someone outside that group, then there is less of a need to “play nice”.

More intelligent people than me might have other complaints about his reasoning. However, one of the most significant things is that he never actually says “why” Indians defect all the time. Towards the beginning of the book, he says, “I am what I am. We are what we are.” But that is not a very satisfying answer.

Why this book may not be for you

Before you pick up this book, remember these things:

1. This book was by an Indian, for Indians. It is not meant as an explanation for outsiders.

2. The author is a highly educated, highly travelled, and from a sub-section of Indians who often discuss these issues with academic detachment. You could imagine yourself as a guest to a dinner party at an Indian home when one guest begins making all these points.

You should not read this book in preparation to come to India. As I mentioned in a previous article, generalizations can be helpful, but only if they offer a helpful starting place. If you are just beginning your journey, starting with the assumption that “Indians will rip me off at every chance they get” is not a helpful place.

You should also not read this book if you are in a particularly difficult time in India, such as right after experiencing a few culture attacks. While you may closely identify with the book, it doesn’t offer any helpful tips for an outsider trying to come to terms with these things.

If neither of these things apply to you, and you can appreciate the book as interesting dinner conversation, then please enjoy it. But remember that it is not meant for you.

Buy it on Amazon.com or Amazon.in

Don’t forget to subscribe for all the latest posts!

Excellent review. I have wanted to read this book for some time but am unable to find it abroad. I am also a bit off-put by it’s title.

I totally agree with your comment that it’s really “group/family needs”. In our family, it is the immediate family and then with the extended the circle gets wider and wider. Each circle is like a priority level. As we all know, Indians will do anything for their kids!

Yeah, the book is not for the faint at heart! It seemed to me that the author had placed this individual framework on top of all of Indian society which never fits well. Thanks for the feedback!